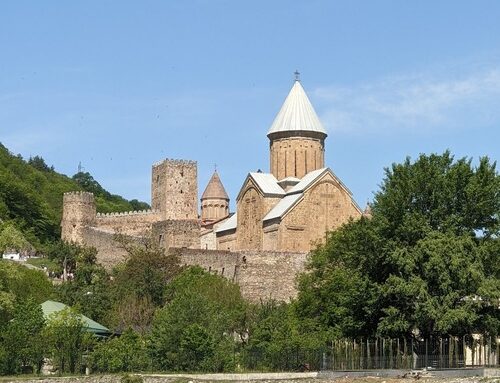

Jvari Monastery: Georgia’s Sacred Hilltop

Perched on a cliff where two rivers meet, this 6th-century church marks the spot where Georgia’s patron saint planted the cross that converted a kingdom — and offers the most iconic view in the country.

There’s a moment on every first visit to Georgia when the country clicks into focus. For many travelers, that moment happens at Jvari monastery. You stand on a windswept hilltop, the stone walls of a 1,500-year-old church behind you, and look down at two rivers merging into one, the ancient town of Mtskheta spread across their banks, mountains rising beyond. This is the view that appears on postcards, in guidebooks, and in the imagination of every Georgian abroad.

But Jvari is more than a viewpoint. This modest stone church, its form perfected across fourteen centuries of weathering, stands where Saint Nino planted a wooden cross in the 4th century — the act that marked Georgia’s conversion to Christianity. The building itself revolutionized Caucasian architecture, creating a template that churches across the region would follow for centuries. And the view from its terrace inspired one of Russian literature’s most famous poems.

Understanding Jvari means understanding Georgia. Here, in one compact site, you find the threads of religion, history, architecture, and landscape that weave through everything else you’ll encounter in this country.

The Story of Jvari

Saint Nino and the Wooden Cross (4th Century)

Georgia’s conversion to Christianity begins with a woman, a vision, and a cross made of grapevines.

According to tradition, Saint Nino — a young woman from Cappadocia — arrived in Georgia around 320 AD with a mission to spread Christianity. She carried a cross made from grapevine branches, bound with her own hair (an image you’ll see throughout Georgia, the bent crossbar distinctive).

Nino performed healings, won converts, and eventually baptized the Georgian royal family. King Mirian III and Queen Nana embraced Christianity, making Georgia one of the first nations to adopt the faith as its state religion — predating Rome’s conversion.

To mark this triumph, Nino erected a large wooden cross on the hilltop overlooking Mtskheta, then Georgia’s capital. The cross was said to emit light and work miracles. Pilgrims came from across the region to venerate it.

For two centuries, the wooden cross stood alone on this ridge. Then, in the 6th century, Georgia’s rulers decided to give it a permanent home.

The Small Church of Guaram (545–586 AD)

Prince Guaram I, ruler of Kartli, constructed the first stone church on the site sometime in the mid-6th century. This “Small Jvari” (which partially survives today, just north of the main church) was built specifically to shelter and honor Nino’s cross.

The small church established the site’s sacred significance in stone. But Guaram’s son would think bigger.

The Main Church (586–605 AD)

Stepanoz I, Guaram’s son and successor, commissioned the monumental church that dominates the hilltop today. Construction took nearly two decades, from 586 to approximately 605 AD.

The result was revolutionary. The architect (whose name is lost) created something new: a church form so perfectly balanced, so harmoniously integrated with its setting, that it became the model for churches across Georgia and the Caucasus for centuries.

The building surrounds the original wooden cross (or its successor), which stood on an octagonal pedestal in the center of the interior. Visitors could circumambulate the sacred relic while the architecture focused attention and light upon it.

This “Jvari type” — a tetraconch (four-apsed) plan with corner chambers and a central dome — influenced countless later churches, including Samtavisi, Ateni Sioni, and buildings as far as Armenia.

UNESCO Recognition

In 1994, UNESCO inscribed Jvari Monastery (along with Mtskheta’s other historic monuments) as a World Heritage Site, recognizing its “outstanding universal value” as a masterpiece of medieval religious architecture and a place of exceptional cultural significance.

What Makes Jvari Architecturally Important

For visitors without architecture backgrounds, Jvari’s significance isn’t immediately obvious. It’s a stone church — beautiful, but seemingly simple. Understanding what the builders achieved helps appreciate what you’re seeing.

The Problem

Before Jvari, architects struggled with a challenge: how to place a dome over a space that wasn’t circular. Domes sit naturally on round walls, but churches typically needed rectangular interiors for liturgical purposes. Solutions were awkward — domes perched on ungainly transition zones, interiors chopped into uncomfortable segments.

The Solution

Jvari’s architect solved this with elegant geometry. The plan uses four apses (curved spaces projecting from a central square), with smaller chambers filling the corners. This creates an interior that flows naturally into the dome overhead while providing distinct spaces for liturgical functions.

The exterior reflects the interior logic: the building’s silhouette rises organically to the dome, each element supporting the next. Nothing feels forced or awkward.

The Result

Standing inside Jvari, you experience unusual spatial harmony. The dome floats overhead, supported visually by the apses below. Light enters through carefully placed windows, illuminating the octagonal pedestal at center (where the cross once stood). The proportions feel inevitable, as though no other arrangement was possible.

This wasn’t just aesthetically successful — it was structurally sound. Jvari has survived 1,400 years of earthquakes, invasions, and weathering with its basic form intact.

Influence

The “Jvari type” became the standard for Georgian church architecture. Variations spread across the Caucasus and influenced Byzantine builders. When you visit later Georgian churches — Samtavisi, Ateni, Nikortsminda — you’re seeing Jvari’s descendants.

The View: Where Two Rivers Meet

The Famous Confluence

The terrace in front of Jvari offers Georgia’s most iconic view. Below, the Mtkvari River (known as the Kura in Azerbaijan) meets the Aragvi River, their waters merging in a visible line of different colors — the Mtkvari’s gray meeting the Aragvi’s blue-green.

On the peninsula formed by this confluence sits Mtskheta, Georgia’s ancient capital, with the great Svetitskhoveli Cathedral visible from above. Beyond, the Lesser Caucasus mountains form the horizon.

This view — church, rivers, town, mountains — encapsulates Georgia’s geography and history in a single frame. It’s been photographed millions of times, but the experience of standing there, wind in your face, never becomes routine.

Lermontov’s Poem

The Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov (1814–1841) visited Georgia during his military service and was captivated by this exact view. His poem “Mtsyri” (The Novice), published in 1840, describes Jvari’s setting in its famous opening lines:

A few years back, where, rushing, loudly blend

Aragva’s and the Mtkvari’s waters

There was a cloister…

The poem tells of a young monk who escapes his monastery to experience freedom, only to die within sight of its walls. Whether or not Jvari was literally the setting, Lermontov’s description immortalized this landscape in Russian literature.

For Russian-speaking visitors especially, Jvari carries literary as well as religious significance.

Visiting Jvari Monastery

Location

Jvari sits atop a ridge approximately 7 km from Mtskheta town center, at an elevation of about 70 meters above the river valley. The monastery is visible from Mtskheta below, and Mtskheta is visible from Jvari above — they’re meant to be experienced together.

GPS Coordinates: 41.8382° N, 44.7332° E

Getting There

From Mtskheta: The monastery is approximately 7 km from Mtskheta center. Options:

- Taxi: 15–20 GEL round trip (including waiting time); negotiate before departing

- Walk: Possible but steep (2 hours up); not recommended in summer heat

- Organized tour: Most Mtskheta tours include Jvari

From Tbilisi:

- By car: 25 km, approximately 30–40 minutes via the highway

- By taxi: 40–60 GEL round trip from Tbilisi (including Mtskheta is more efficient)

- By tour: Most half-day and full-day Mtskheta tours include Jvari

Important: There is no public transport directly to Jvari. Marshrutkas from Tbilisi stop in Mtskheta but don’t climb to the monastery.

Hours and Access

Jvari is open daily from approximately sunrise to sunset. As an active place of worship, the church may occasionally close for services.

Entrance: Free (donations welcomed)

What to See

The Main Church: Enter through the south portal to experience the interior. Note:

- The octagonal pedestal in the center — where the original cross stood

- The dome overhead with its harmonious proportions

- Relief carvings on the exterior, including depictions of the church’s builders

- The stonework, remarkably preserved after 1,400+ years

The Small Church (Guaram’s Chapel): Just north of the main church, the older, smaller structure survives partially. It offers insight into the site’s earlier phase.

The Terrace: Don’t miss the viewpoint terrace extending from the church. This is where you’ll see the famous confluence view.

The Defensive Walls: Remnants of medieval walls surround the site, added in later centuries for protection.

Time Needed

- Quick visit (view + church exterior): 20–30 minutes

- Standard visit (including interior): 45 minutes to 1 hour

- Photography-focused visit: 1–2 hours

Dress Code

As an active Orthodox church, modest dress is required:

- Women: Cover shoulders and knees; head covering appreciated

- Men: Long pants preferred; remove hats inside

Scarves are sometimes available at the entrance for those who need them.

Best Time to Visit

For photography:

- Sunrise: Dramatic light on the church and eastern-facing view; virtually empty

- Golden hour (late afternoon): Warm light, river views beautifully lit

- Avoid: Midday in summer (harsh light, crowded with tour buses)

For atmosphere:

- Early morning or late afternoon avoids the largest crowds

- Weekday mornings are quietest

Seasons:

- Spring (April–May): Green valleys, wildflowers, comfortable temperatures

- Summer (June–August): Hot midday; visit early or late

- Autumn (September–October): Golden light, harvest colors in valleys

- Winter (November–March): Fewer visitors, potentially dramatic skies; can be cold and windy

Photography Tips

Jvari is one of Georgia’s most photogenic sites. To capture it well:

The Classic Shots

Confluence view: Stand on the terrace facing southeast. The two rivers, Mtskheta, and distant mountains create the iconic composition. Best light: morning (rivers front-lit) or golden hour (warm tones).

Church exterior: The south and east facades are most photogenic. Include sky for drama; use people for scale.

Interior: Challenging due to dim light. Tripod or steady hands; high ISO; focus on the dome and light through windows.

Church with mountains: Position yourself east of the building to include Caucasus peaks in the background.

Technical Considerations

- Wide-angle lens useful for architecture and landscape

- Telephoto for details (carvings, distant Mtskheta)

- Polarizing filter helpful for sky and river reflections

- Tripod recommended for interior and low-light exterior

- Wind is common; secure equipment

Crowds

Jvari sees many visitors, especially when tour buses arrive (typically 10:00–14:00). For empty shots, arrive at sunrise or visit late afternoon.

Combining Jvari with Mtskheta

Jvari and Mtskheta belong together — one is incomplete without the other. A logical half-day itinerary:

Option 1: Jvari First Start at Jvari in early morning (best light for photos, fewer crowds), then descend to Mtskheta for Svetitskhoveli Cathedral and town exploration.

Option 2: Mtskheta First Explore Svetitskhoveli and Mtskheta in the morning, lunch in town, then ascend to Jvari for golden hour light on the confluence view.

Full Day Extension: Add Samtavro Monastery (in Mtskheta), the Bebris Tsikhe fortress ruins, or continue to the Georgian Military Highway toward Ananuri or Kazbegi.

Nearby Attractions

Svetitskhoveli Cathedral (7 km in Mtskheta): Georgia’s most important cathedral, burial place of the robe of Christ. UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Samtavro Monastery (7 km in Mtskheta): Where Saint Nino lived and prayed; burial place of King Mirian and Queen Nana.

Bebris Tsikhe (3 km): Medieval fortress ruins with views over Mtskheta.

Shiomghvime Monastery (13 km): 6th-century cave monastery in a dramatic gorge.

Zedazeni Monastery (15 km): Hilltop monastery with panoramic views, rarely visited.

The Meaning of Jvari

“Jvari” means “cross” in Georgian. The name reflects the site’s founding purpose: to honor the wooden cross Saint Nino erected here.

But the word carries weight beyond this single location. The cross (jvari) appears throughout Georgian culture — on flags, churches, graves, roadside shrines. It represents not just Christianity in general but Georgia’s specific, ancient, and continuous relationship with the faith.

When you stand at Jvari, you’re standing at the symbolic origin of that relationship: the place where, according to tradition, a woman from Cappadocia planted a grapevine cross and changed a nation’s history.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does “Jvari” mean?

“Jvari” (ჯვარი) means “cross” in Georgian. The monastery is named for the wooden cross Saint Nino erected on this hilltop in the 4th century to mark Georgia’s conversion to Christianity.

Is Jvari a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

Yes. Jvari was inscribed as part of the “Historical Monuments of Mtskheta” UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994, along with Svetitskhoveli Cathedral and Samtavro Monastery.

How old is Jvari Monastery?

The main church was built between 586 and 605 AD, making it approximately 1,420 years old. The smaller church nearby dates to the mid-6th century (545–586 AD).

Why is Jvari architecturally important?

Jvari pioneered a new church form — the “Jvari type” — that elegantly solved the problem of placing a dome over a non-circular space. This design influenced church architecture throughout Georgia and the Caucasus for centuries.

Can I see Mtskheta from Jvari?

Yes. The terrace in front of Jvari offers panoramic views of Mtskheta below, the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi rivers, and the surrounding mountains. This is Georgia’s most famous view.

How do I get to Jvari from Mtskheta?

Jvari is 7 km from Mtskheta center. There’s no public transport; options are taxi (15–20 GEL round trip), organized tour, or a steep 2-hour walk. Most visitors combine Jvari with a Mtskheta tour from Tbilisi.

Is there an entrance fee for Jvari?

No. Jvari is free to enter. Donations are welcomed and support the monastery.

What should I wear to visit Jvari?

Modest dress is required: shoulders and knees covered for women (head covering appreciated), long pants for men. Remove hats inside the church.

How much time do I need at Jvari?

Allow 45 minutes to 1 hour for a standard visit, including the church interior and viewpoint. Photography enthusiasts may want 1–2 hours, especially during golden hour.

What is the connection between Jvari and Lermontov?

Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov described Jvari’s setting in his famous 1840 poem “Mtsyri” (The Novice), immortalizing the view of the river confluence in Russian literature.

Visit Jvari on a Mtskheta Tour

Jvari and Mtskheta together offer the perfect introduction to Georgian history, religion, and landscape. In a single half-day excursion from Tbilisi, you can stand where Saint Nino planted her cross, gaze down at the confluence that has defined this landscape for millennia, and walk the streets of Georgia’s ancient capital.

We include Jvari in our Mtskheta day tours, combining the hilltop monastery with Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, Samtavro Monastery, and optional extensions to other nearby sites. The journey takes you through the layers of Georgian history in a single morning or afternoon.

Georgia Tours has been sharing Mtskheta and Jvari with travelers since 2011. We know the best times to visit, the angles for perfect photographs, and the stories that bring these ancient stones to life. Contact us to plan your journey to the heart of Georgian Christianity.