Samtskhe-Javakheti

General information about Samtskhe-Javakheti

Samtskhe-Javakheti is one of the largest regions of Georgia. Its total area comprises 6 421 sq/km and its capital and administrative center is the town of Akhaltsikhe. To the north-west, the region is bordered by Guria and Imereti; to the north – by the region Shida Kartli; to the east by Kvemo Kartli; to the south by Armenia and Turkey and to the west by Adjara.

Samtskhe-Javakheti region consists of six districts: Akhaltsikhe, Adigeni, Aspindza, Akhalkalaki, and Ninotsminda.

The region is ethnically diverse with a mix of Georgians, Armenians, Greeks, Ossetians, Russians, and Ukrainians. Samtskhe-Javakheti is the oldest historic territory of Georgia and is considered the cradle of Georgian culture.

The ancient Georgian tribes dwelled in this territory. St. Nino of Capadoccia, the convertor of Georgia to Christianity, entered the country with a holy cross made of vine stems tied by her own hair via the misty mountains of Javakheti. According to literary data and folk narrative, it is the birthplace of the most famous Georgian poet – Shota Rustaveli – the area where the unique masterpieces of Georgian culture were born. Samtskhe-Javakheti territory encompasses a part of Meskheti, Javakheti and Tori.

Civilization began here some 4 000 years ago when a major tribal union arose known as “Diaokhi”. From VI to IV centuries BC, Samtskhe-Javakheti was a part of the Georgian kingdom Iberia (Kartli) which constituted the territory of eastern and southern Georgia. In the XII century “the golden age” – during the renaissance of Georgian statehood, the great king David IV The Builder consolidated Meskheti leading to a cultural revival of the country and this region. During the mid-XIII century, ferocious Mongol hordes invaded Georgia and took control.

They were followed by a Turkish invasion, pursuing a policy of Islamization. Some Georgians adopted Islam; others escaped it by migrating to Kartli and Imereti. Throughout the XIX century, Georgia’s population grew considerably as Christian Armenians fled from Islamic Turkey. As a result of this history, there are unique of different cultural influences as seen in the architecture and monuments.

Religion

Most ethnic Georgians associate themselves with the Georgian Orthodox church, some Georgians are Catholics. In the XVI-XVII cc. Islamization of the region commenced. According to a concordance between the Turkish and Roman Catholic Church, the Turks could not oppress the Roman Catholics. In order to preserve the Christian faith, some Georgians staying in the region turned to Roman Catholicism. Armenians of the region, mostly belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church. In addition, there is a small number of ethnic Russian believers from two dissident Orthodox schools: the Molokans Staroveri (Old believers) and Dukhobors.

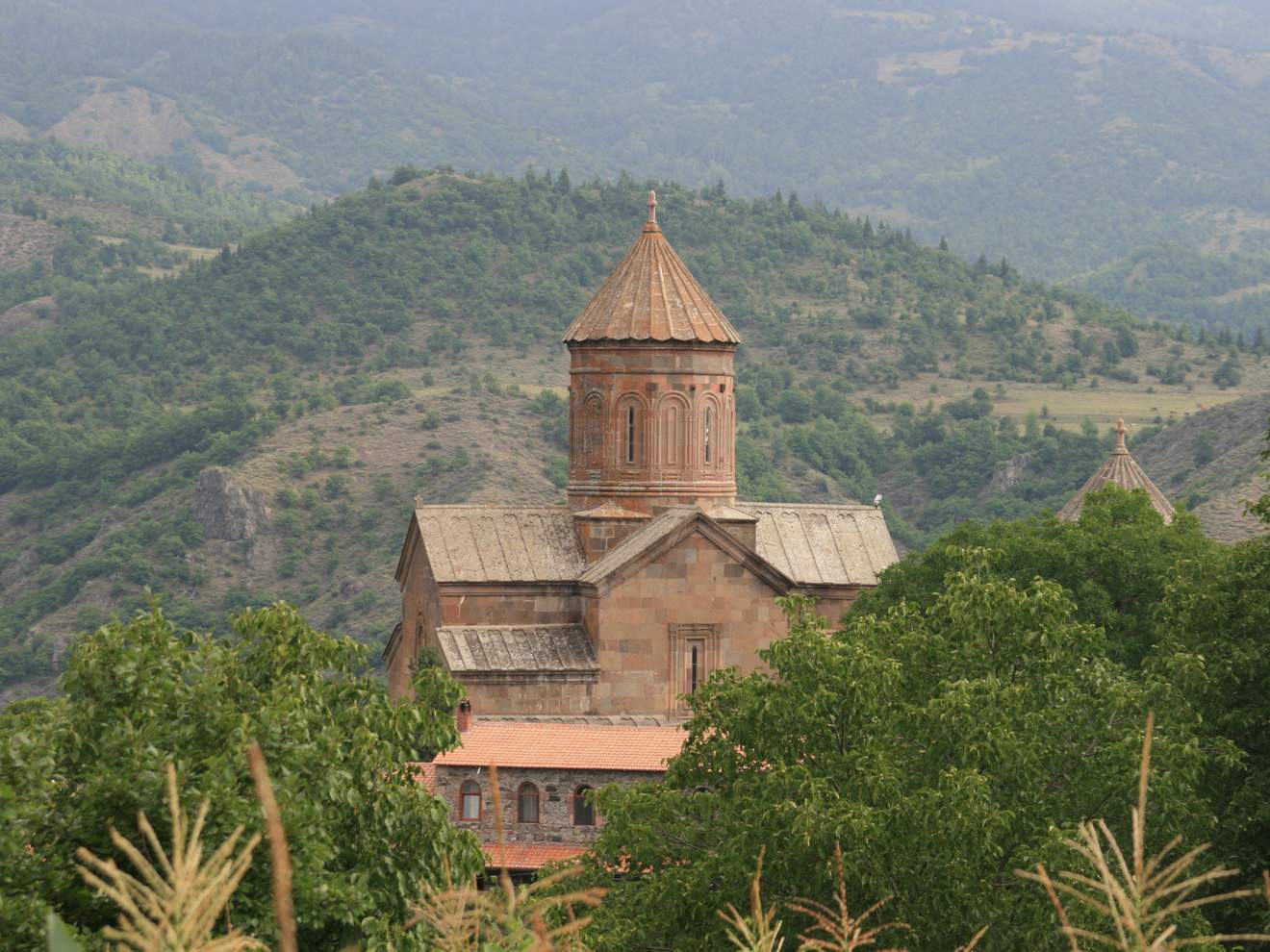

Local Architecture

The villages and abandoned dwelling places of Meskheti have preserved many architectural monuments and household goods depicting the ancient way of life. These complexes prevailing in Samtskhe-Javakheti represent the culture of Darbazi – peasant dwellings, which existed in Colchis as early as the I century AD and were even common at the beginning of the XX century.

Each building is one-story, usually placed upon a mountain slope or hill, with three walls reaching into the earth. The main factors here are interior and roofing so-called crowns, consisting of horizontally placed wooden piles, arranged in a steeple. A hole is left on its peak for air and light. The crown is square. Below the crown is a hearth where meals are cooked. The dwelling could also house a Meskhetian bakery/bread oven; the hollow deposit for the grain which, in some cases, could hold two tons of wheat, and a stone press and stone cut basin to store cheese.

Darani

Constant attacks by enemies and the population’s struggle for survival created a system of underground dwellings and shelters, the so-called Darani. Daranis represented cell-like shelters interconnected through a complex system of tunnels. They were fitted with an air and water supply network. Entrances to Daranis are still seen in the villages Kuleti, Ipnieti, Shalosheti, Lepisi, and Khizabavra as well as in many other old dwelling sites.

- Vardzia cave monastery complex

- Vanis kvabebi cave monastery complex

- Upper Vardzia monastery

- Tsunda church

- Green monastery

- Timotesubani church

- Sapara monastery

- Zarzma church

- New Zarma church

- Chule church

- St. George’s church in Upper Tmogvi

- Agara monastery complex

- Archangel church of Saro

- Khizabavra catholic church

- Akhaltsikhe catholic church

- Kumurdo cathedral

- Borjomi-Kharagauli national park

- Javakheti protected area

- Tabatskuri-Kstsia protected area

- Sagamo lake

- Abastumani forests

- Adigeni forests

- Slesa fortress

- Atskuri fortress

- Rabati fortress

- Okro (“golden”) fortress

- Khertvisi fortress

- Saro tree fortresses

- Tmogvi fortress

- Abuli fortress

- Shaori fortress

- “Darns” in Lepisi

- “Darns” in Khizabavra

- “Baiebi” complex

- Uraveli

- Zveli

- Khizabavra

- Saro

- Upper Tmogvi

- Agara

- Lepisi

- Borjomi

- Likani

- Tsagveri

- Bakuriani

- Abastumani